Thirty years ago today, Ayrton Senna put in a sublime drive to win a rain-affected 1993 Japanese Grand Prix in his penultimate start for McLaren. It was the Brazilian’s fourth victory of a season otherwise dominated by the Williams FW15C, and once again he beat the odds on a day when driver skill and sheer chutzpah counted for much.

But that race at Suzuka is remembered as much for what happened afterwards, when Senna triggered a verbal jousting match with a newcomer he’d come across in the course of the race. Their debate ended with Senna launching a physical assault that landed him in hot water with the FIA.

The debutant who got his attention was Eddie Irvine. Forgotten in Europe, at the time the Ulsterman was in the third year of his exile in Japanese Formula 3000. Racing against others who had run out of options at home, as well as veteran local heroes, he was earning a good living, and had pretty much given up any thoughts he’d had of ever making it to F1.

Everything changed for Irvine at the 1993 Le Mans 24 Hours, where he was one of the stars of the race. During the weekend he bumped into his one-time European F3000 employer and manager Eddie Jordan. The pair had been estranged for some time, but after this reunion the possibility of Irvine competing in the final two Grands Prix of 1993 emerged, if he could bring some backing. He was able to find some support from Cosmo Oil, backer of his Cerumo F3000 team, but he was still a little short, so he dipped into his own savings to make up the difference.

Nobody bothered to tell the team’s main sponsor, Sasol, that the stickers of another oil company were now on the car’s front wings…

The car had previously been driven by Ivan Capelli, Thierry Boutsen and, more recently, by Irvine’s fellow Japanese F3000 expats Marco Apicella and Emanuele Naspetti. None of them had been able to do much with it, and even the promising Rubens Barrichello — on board at Jordan all season — had yet to score a point.

A test at Estoril proved disappointing as Irvine got used to traction control and struggled both with a difficult car and back pain caused by an awkward seating position, thanks to his long body and short legs. He was so disappointed that when we spoke on the phone that week he said it was the worst decision he’d ever made.

«I’m in a very strong position in Japan,» he said. «I’ve got a very good sponsor, and a good team. The racing here is very competitive, and I run at the front all the time. I don’t want to get my arse into F1 just for the sake of being there!

«Whatever I’m driving, as long as I’m happy with the job I’ve done, that’s all I care about. But obviously, to everybody else, if you’re not in F1, you’re a nobody.»

On Thursday we headed via bullet train to Suzuka where, as for the domestic races, we were sharing a room at the Circuit Hotel. It seemed like any F3000 weekend. Little did we know how it would turn out.

«My back was in agony. After 10 laps I thought I couldn’t take any more» Eddie Irvine

Fortunately, when Irvine headed out on track, everything fell into place. Over three seasons he’d competed in 11 F3000 races at Suzuka (pictured below earlier in 1993), and done countless days of testing, with endless sets of Dunlops available. He knew every inch of the place, and on local qualifying tyres F3000 lap times were comparable with F1. It all seemed very normal for him.

At the end of the first free practice session on Friday morning, the times read Hill, Hakkinen, Alesi, Schumacher — and Irvine. Mechanical problems dropped Senna and Prost down the order, but, local knowledge or not, it was an impressive performance. Team-mate Barrichello, meanwhile, was new to the track, and took time to get up to speed. Irvine ultimately qualified eighth. It was a remarkable position for a Jordan-Hart that had not scored a point all season.

To put it into perspective, you need to recall that at the time, Barrichello was the next superstar, the logical successor to Senna. He’d destroyed Capelli and Boutsen, but only once, in France, did he qualify inside the top 10, and elsewhere the quicker Jordan was usually between 13th and 17th. He was undoubtedly revved up by Irvine’s presence, and pulled out all the stops to take 12th — and promptly fell off the road. Suddenly, everyone took notice of the newcomer.

By taking the outside line at Turn 1 Irvine jumped as high as fifth at the start, passing Damon Hill and Schumacher. It took the Benetton a couple of laps to repass him, and it was another four before Hill’s Williams made it by. After Schumacher crashed and some of the top guys pitted for tyres, Irvine rose once again to fourth place, at which point it started to rain. The slower pace came as a huge relief, because «…my back was in agony. After 10 laps I thought I couldn’t take any more.»

Knowing how quickly the track could change, Irvine wanted to come straight in, but the team kept him out as it first wanted to service Barrichello, then running ninth. By the time Eddie was allowed in, the track was completely awash, and as he tiptoed round he lost great chunks of time. He was the last of those still in the race to pit, and the damage had been done; he’d dropped to 10th, while Rubens rose to sixth.

Still suffering with back pain, Irvine was on the fringes of the points when leader Senna appeared in his mirrors late in the race. With low fuel and on a drying track Eddie had good pace, and Senna only got by when the Jordan ran wide on oil at Degner. Irvine then found himself behind the McLaren and keen to go faster and attack those ahead, specifically Hill.

So in an unprecedented move he unlapped himself at the chicane, and began to pull away. He then ran wide again, and was repassed, making sure that he left Senna room before he scrambled back onto the track.

He then got into a battle with Derek Warwick. Irvine felt that Warwick had been a little overaggressive, and their battle ended when he gave the Footwork driver a friendly tap at the chicane, sending him spinning. After all those races at Suzuka, he knew every trick. Warwick was left fuming at the trackside.

Right at the end Irvine unlapped himself from Senna a second time, under instructions from the team, and he eventually finished sixth behind Barrichello. He thus joined the elite group of drivers who’d scored points on their debut — much harder then, when it was only the top six — but his overall feeling was one of frustration, largely because of the time lost when he was stuck out on slicks.

After the race he was called to see the stewards over the Warwick incident. They accepted his innocent explanation that Derek had put him off the road, he’d got dirt on his tyres, and hadn’t been able to brake effectively when he arrived at the chicane. It was a lucky escape…

Following his victory celebrations Senna lambasted Irvine in the press conference. He then headed to the room occupied by Karl-Heinz Zimmermann, Bernie Ecclestone’s hospitality host. There he hooked up with Gerhard Berger and, already fuelled by the podium champagne, had a glass of schnapps. It was while they watched a re-run of the race — and Senna complained about his tussle with Irvine — that the Austrian began teasing his old pal.

«You know how Gerhard is, he can wind people up!» Zimmermann recalls. «He looked at Ayrton and said, ‘Who was it who blocked you? Eddie did a good job today, huh?’ You could see the colour change. And out he went and down the stairs. I couldn’t believe it!»

«I know exactly what schnapps does,» says Berger. «For Austrians it’s our home drink, and it creates some aggression in you! I said, ‘Don’t just talk about it, just get the job done.’ And suddenly he disappeared.»

«You want to do well. I understand, because I’ve been there, I understand. But it’s very unprofessional» Ayrton Senna

Senna marched straight to the Jordan office. I was already there, having just finished interviewing Irvine about his amazing afternoon. Then the door swung open and Ayrton charged in, followed by McLaren engineer Giorgio Ascanelli and team manager Jo Ramirez.

Eddie Jordan had left straight after the race for a holiday in Australia, and there were about six of us in the room, including commercial director Ian Phillips, Barrichello, and his manager. Senna looked around before his eyes finally alighted on Irvine, who had already changed out of his overalls.

I switched my tape recorder back on just as Ayrton began to tell the upstart his fortune. We watched transfixed as they engaged in verbal combat, Senna peppering his argument with expletives while he pointed out that he was the leader of the race. Irvine refused to budge and said simply that he was faster at that point.

Senna: I tell you something. If you don’t behave properly in the next event, you can just rethink what you can do. I guarantee you that.

Irvine: The stewards said, ‘No problem, nothing was wrong’.

Senna: Yeah? You wait ’til Australia, mate. You wait ’til Australia, and the stewards will talk to you. Then you tell me if they tell you this.

Irvine: Hey, I’m out there to do the best I can for me.

Senna: This is not correct. You want to do well. I understand, because I’ve been there, I understand. But it’s very unprofessional. If you are a backmarker, because you are about to be lapped…

Irvine: But I would have followed you if you had overtaken Hill!

Senna: You should let the leader go by…

Irvine: I understand that fully!

Senna: …and not come and do the things you did. You nearly hit Hill in front of me three times, because I saw, and I could have collected you and him as a result, and that’s not the way to do that.

Irvine: But I’m racing! I’m racing! You just happened to…

Senna: You’re not racing! You’re driving like a ****ing idiot! You’re not a racing driver, you’re a ****ing idiot!

After that, there was no way back. Although Irvine didn’t swear in return, he refused to concede that he’d done anything wrong, and Senna was dumbfounded at the newcomer’s nonchalance. The debate finished with the following exchange.

Senna: You be careful guy.

Irvine: I will, I’ll watch out for you.

Senna: You’re going to have problems, not with me only, but with lots of other guys, and also the FIA.

Irvine: Yeah?

Senna: You bet.

Irvine: Yeah? Good.

«He was left-handed and he went with the right hand, and when Eddie tried to deviate from that he came with the left!» Rubens Barrichello

Senna: Yeah. It’s good to know that.

Irvine: See you out there.

Senna: It’s good to know that!

Irvine: See you out there…

As things built to a climax Senna lunged clumsily at Irvine, who was sitting on a table.

«You could see that something was coming,» recalls Barrichello. «I never saw him so agitated, and he had just won the race, so I don’t know what the point was. He was left-handed and he went with the right hand, and when Eddie tried to deviate from that he came with the left! It was a big bang and Eddie just fell down.»

The McLaren guys dragged Senna away, and within minutes the whole paddock knew what had happened.

«People came back and told us he’d had a fight with Eddie,» smiles Berger. «The schnapps was definitely the reason for his reaction! On this day it was the right medicine for the problems he had.»

I headed back to the media centre and quickly typed up a transcript of my recording. A re-enactment was later staged in the Jordan offices for those who had missed it, with Irvine playing himself and team press officer Louise Goodman as Senna.

The next day, we took the bullet train back to Tokyo. This being the pre-internet era, we didn’t know that the fight had become the biggest sports news story of the day in Europe.

«I was on a flight from Osaka to Cairns,» recalls Jordan. «The next morning I met Ken Tyrrell for breakfast and he said, ‘My God, you’re in the news’. I had no idea! I rang home, and they said, ‘This is amazing’.»

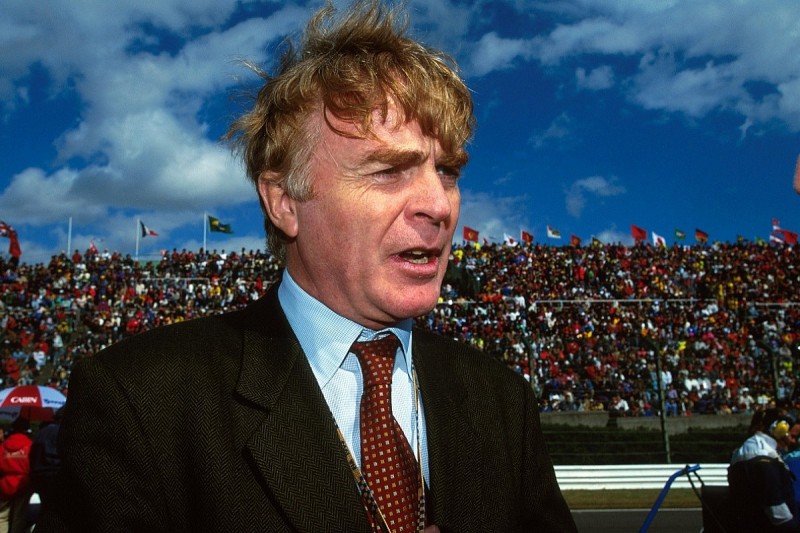

FIA president Max Mosley had been at Suzuka, but left before the end of the race. Intrigued about what might happen next, on Monday afternoon I rang his London office to ask if he was back yet. His secretary told me he was still in Tokyo. «That’s handy, so am I,» I replied.

I called him at his hotel and asked if he knew about the confrontation. Only very vaguely, he said. I told him I had a tape and, more than a little intrigued, he said he’d like to hear it.

I got on my bicycle, rode around to the hotel, and went up to Mosley’s room, where he greeted me in jeans and T-shirt. Over a cup of tea we listened to the tape, which ended amid dramatic scuffling and shouting as Senna piled in. «Hmmm,» said Max. «I think we’re going to have to do something about this. Can you make me a copy?»

I managed to get the transcript into the Daily Express, but a call to the BBC led nowhere. Then in the early hours landline my phone rang. It was a Radio 2 producer saying he’d just got my message. The drive-time sports programme was just coming to an end, and Senna/Irvine was the main topic of conversation. Would I be prepared to talk about it?

I was still half-asleep, but could hardly refuse, and suddenly there I was on air. The presenter asked me to describe what had happened, and then the subject of the tape came up — and he asked me for a sample. I put my recorder up to the phone, pressed play, and of course Ayrton Senna started effing and blinding to a few million Brits on their way home from work. ‘Oops’, I thought. «That was brilliant!» said the producer as he said goodbye.

«The ‘fight’ is 0.0001% of what I remember about the race — it’s totally not important» Eddie Irvine

Prior to the Australian GP Irvine stayed in Macau for a week, and was pretty much out of phone contact. When he arrived in Adelaide, he was virtually mobbed by the media. Overnight he’d become a sought-after commodity, although typically he was totally unimpressed by events.

Through the Adelaide weekend the main topic of conversation was the possible sanction for Senna: would he receive a ban that would compromise the start of his 1994 season at Williams? Ayrton defended his actions against Eddie, noting somewhat uncharitably that «the people round him were not in a normal state; they were drunk and no one did anything to prevent what occurred». He went on to score an emotional final win for McLaren, the last of his career.

Keen to prepare their defence, Senna’s management offered to buy a copy of the tape. I sent it along with a bill for a token £80 for my trouble. Later a cheque from ‘Ayrton Senna Productions’ arrived, via a Liechtenstein bank. Alas, my local NatWest rejected it, and I still have it in a drawer somewhere.

After Adelaide, Senna had to interrupt his Brazilian winter holiday to head to France for the 9 December gathering, at which the tape was the main exhibit. He escaped with a suspended two-race ban as Mosley noted «what happened cannot be allowed in the sport».

Thirty years on the world has changed – think of the fuss over the recent Lance Stroll incident – and a similar offence would attract a much more severe punishment.

«It would be nice to see fisticuffs at dawn, wouldn’t it?» smiles former Jordan technical director Gary Anderson. «People were real human beings then. It’s just a sniping thing these days.»

There’s no denying that the momentum from Suzuka led directly to Irvine abandoning Japan for a full-time Jordan drive in 1994. But he has few fond memories of the race.

«Suzuka ’93 is so long ago now that it doesn’t register,» he says. «It’s like something that happened to somebody else — it didn’t happen to me! The ‘fight’ is 0.0001% of what I remember about the race — it’s totally not important.

«It got me attention, but for the wrong reasons. It was my first grand prix and I went round the outside of four or five cars in the first two corners, and that’s what people should have been talking about. I don’t think it did me any good, I really don’t.»

The irony in all this was that Irvine had always looked up to Senna. He’d followed in his wheeltracks at Van Diemen in FF1600 and West Surrey Racing in F3, and at one stage his yellow helmet design was very close to Senna’s.

«He had been my favourite driver, and after that I thought the guy was an arrogant prick,» he adds. «But I did talk to him in Brazil at the start of 1994, and he was fine about it. He said it’s over, something like that.»